ALTERNATE SIDES ART PROJECT

The Alternate Sides Art Project explores themes of impermanence, transformation, and interaction. Each piece begins with an original composition that serves as a foundation for evolution, inviting engagement and collaboration. This dynamic and participatory approach ensures the artwork remains in a constant state of flux, never settling into a fixed or final form.

The project reflects diverse perspectives and interpretations, with its iterations documented as a record of its evolution. Through this process, Alternate Sides highlights the transient nature of art and the power of communal involvement, challenging traditional notions of artistic creation and ownership. By embracing change, it offers a fresh perspective on how art can connect and resonate with others.

__________________________________________________________

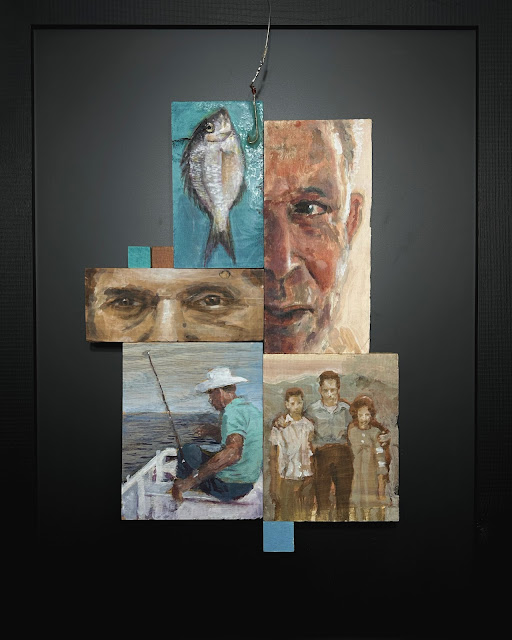

AYUB

Acrylic on modular reclaimed wood blocks + collage media. 18 x 24”

Assembled. 2024

__________________________________________________________

MAMÁ

Acrylic on modular reclaimed wood blocks + collage media. 18 x 24”

Assembled. 2024